The Alexander Film Company: Creating Lasting Impressions.

by Tim Reed

Intermission by Alexander. The b/w scans are from a group of films the author uncovered recently in a warehouse.

A good percentage of now-classic intermission films, or "clocks", shown at countless drive-ins over the years, were produced by the Alexander Film Co. of Colorado Springs, CO. There were several film companies, in cities like Chicago, New York and San Francisco, that also produced intermission ads for drive-ins, but the Alexander company was, by far, the largest. If you've ever been to a drive-in, you likely have seen some version of a "10 minutes 'til showtime", a "visit the refreshment stand" or a "replace the speaker on the post" film. Even if you've never experienced a drive-in, there are several video collections of these films on the market.

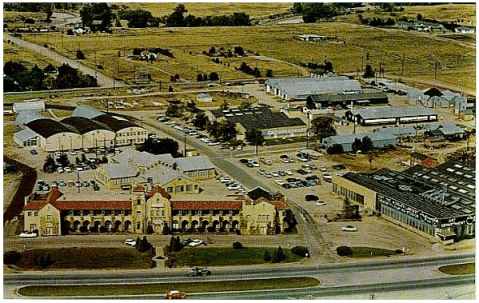

The huge Alexander facility occupied 18 acres. Several stages can be

seen on the lot in this photo.

The sign on the group of buildings at the lower right says, "Art Department"

As 'cheesy' as intermission films may appear today, it cannot be denied that they all featured extremely high production values, first-class animation, sound work and opticals. Present day viewings must be held with the knowledge that the situations, wordings and styles used in these films were then in vogue and were considered very progressive. When new, they were indistinguishable from their best television counterparts (probably because Alexander produced many of those, too).

Intermission and advertising films in production! A typical day on

the

Alexander stages: multiple productions working simultaneously.

The Alexander company, aka Motion Picture Alexander Corp., began in 1919 and eventually became heavily involved in commercial production for national accounts. They were the world's largest producer of screen ads for the theatre industry and by 1955, had agreements with 2,500 drive-ins. It was estimated that 10,000,000 people a week saw their ads.

HOW INTERMISSION FILMS WORKED

In the late 40s, the Armour company produced a trailer (short advertising film) promoting

their hot dogs. This was distributed free of charge to drive-ins that sold Armour hot dogs

and was run during the intermission break between features. A rapid increase in hot dog

sales was immediately noted by all who ran the film and soon requests for the trailer

poured in from operators all over the country. Other manufacturers followed Armour's lead

and soon several product trailers were in the hands of the drive-ins. This further

increased concession sales and began the trend to advertise on the screen during

intermission.

The Alexander Film Company was engaged in selling screen advertising to local merchants. This involved a nationwide network of salesmen who called on various car dealers, drug stores, laundrys, banks, service stations and the like, to sell them advertising on local screens. This salesman also negotiated contracts with individual drive-ins, for their screen time.

No doubt, generations of snack bar-bound people have heard this announcer (.wav 39K),

inviting them to purchase. Here, engineers are recording his voice directly to 35mm film.

After production, the films were sent to the local theatres, and screened according to a particular schedule (in the mid 50s, this was usually a one week flight, but longer times evolved). Alexander paid the theatres directly for their screen time. This amount varied according to the size and location of the theatre, which reflected the number of people who would potentially see the ads. After the run, the films were requested to be returned to Alexander. It was a popular way for theatre operators to generate extra income.

Sorting and shipping

thousands of screen ads to the nation's drive-in theatres. In the 50s, the Alexander Film

Company routinely shipped out over 160,000 feet of film a day! (Nearly 30 hours

of 35mm film.) They also had either shipping or production facilities, or both, in New

Orleans and New York.

Sorting and shipping

thousands of screen ads to the nation's drive-in theatres. In the 50s, the Alexander Film

Company routinely shipped out over 160,000 feet of film a day! (Nearly 30 hours

of 35mm film.) They also had either shipping or production facilities, or both, in New

Orleans and New York.

ADS AND FOOD MERGE

The screening of merchant ads and concession trailers inevitably came together and the

"clock" was born. Alexander began producing both generic and brand-name-specific

concession trailers to form the core of intermission clock films; within which their

paid-for merchant ads would be showcased. It could be said that the clock trailers were an

additional measure of goodwill extended to the drive-ins, for screening the local ads.

These were, however, also intended to be returned to Alexander after use.

THE AFTERMATH

As the number of drive-in theatres dropped in the 60s and 70s, so did the product from

Alexander. The company was purchased in the early 70s by Bob Olds and Floyd Sparks, who

were previously involved with a competing firm. This generated a flurry of new

intermission films with modernized themes, but with a somewhat lessened quality of artwork

and production values. By the mid 70s, however, demand for the films diminished.

The Alexander company has since changed ownership numerous times, and today is known as "Alexander Film and Video".

Tim Reed